Never Used a Parsing Tool?

- How a Compiler Works

- The Frontend: Lexing, Parsing, AST and Semantics

- Using a Parsing Tool

- The Next Step

- More Information

How a Compiler Works

(Or: How can I use Goldie to create a compiler?)

There's a common misconception that language tools and computer science theory have advanced enough that creating a compiler can be fully-automated. This is not true. Only certain parts of writing a compiler can be automated, and it's only these parts that parsing tools (such as Goldie, GOLD, Lex/YACC, Flex/Bison and ANTLR) automate. A fully-working compiler is a complex program that contains many different parts.

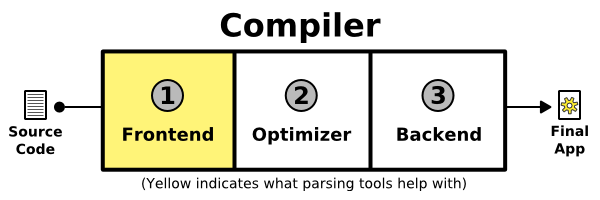

Here is a diagram of the three main parts of a compiler:

-

Frontend: This is the only part of a compiler that automated parsing tools deal with. Even so, automated parsing tools only deal with part of the frontend (see the section The Frontend: Lexing, Parsing, AST and Semantics below).

A compiler takes source code as input and outputs a program. The frontend is the "input" part. It brings in your source code, attempts to understand it, turns it into some sort of internal representation, makes sure everything is correct and gives errors if the source code has a problem.

-

Optimizer: Optimization is an optional, but very common, step. It adjusts the program being compiled so it runs faster, or in some cases, so it takes up less space. Sometimes this is considered to be part of either the frontend or the backend, or split between both.

Automated parsing tools such as Goldie don't help with this step. This has to be either written manually, or an existing optimizer could be used. Either way, this can be a fair amount of work.

-

Backend: The (somewhat amusingly-named) backend is the "output" part of a compiler. It takes the internal representation of the code and converts it into either machine code (possibly for a Virtual Machine) or another programming language. In the case of generating machine code, there's a lot of associated computer science theory (see the books in More Information).

For many languages, the last part of the backend is the linker. The linker combines the many different compiled parts of a program (usually one for each original source file) into one single program. Often, this is done by either a completely separate program (as with many natively-compiled languages, such as D or C/C++) or by the host platform itself (as with dynamically-loaded libraries and many virtual machines such as JVM and .NET).

As with the optimizer, automated parsing tools don't help with this step. The backend has to either be written manually, or an existing backend can be adapted.

The Frontend: Lexing, Parsing, AST and Semantics

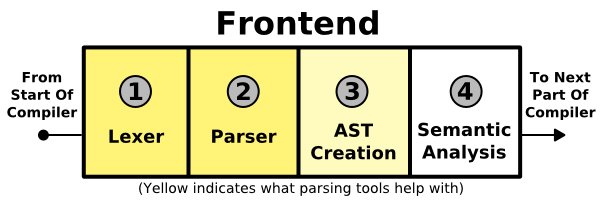

The frontend handles the first step in the compiling process. Like the compiler itself, the frontend is divided into separate steps: Lexing (or "Lexical Analysis"), Parsing (or "Grammatical/Syntactical Analysis"), AST Creation, and Semantic Analysis.

Sometimes people refer to the frontend as a "parser", but that's technically incorrect. The parser is just one of the components in the frontend.

-

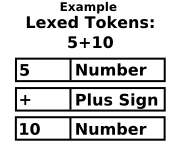

Lexing:

This separates the source into a series of tokens. For instance,

int numApples = 10 gets converted into

"Keyword 'int', Identifier 'numApples', Equals sign, Number 10".

Goldie does this in the Lexer class by using a

DFA.

Lexers are also sometimes called tokenizers and scanners.

You can view the result of this step using the Parse tool

and JsonViewer.

Lexing:

This separates the source into a series of tokens. For instance,

int numApples = 10 gets converted into

"Keyword 'int', Identifier 'numApples', Equals sign, Number 10".

Goldie does this in the Lexer class by using a

DFA.

Lexers are also sometimes called tokenizers and scanners.

You can view the result of this step using the Parse tool

and JsonViewer.

-

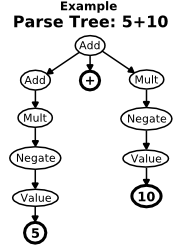

Parsing:

This arranges the lexed tokens into a tree. The structure of the tree is

based directly on the rules in the language's grammar.

Goldie does this in the Parser class by using an

LALR(1) algorithm.

You can view the result of this step using the Parse tool

and JsonViewer.

Parsing:

This arranges the lexed tokens into a tree. The structure of the tree is

based directly on the rules in the language's grammar.

Goldie does this in the Parser class by using an

LALR(1) algorithm.

You can view the result of this step using the Parse tool

and JsonViewer.

Sometimes parsers don't actually build a real parse tree. They may just simply process the tokens as they're being parsed. Or they may merge the parsing step with AST creation (see below) and directly output an AST. Goldie always builds a parse tree, although a future version of Goldie may provide the ability to omit it.

-

AST Creation:

This step is optional and is only sometimes performed by automatic parsers.

Goldie doesn't currently perform this (so you'll have to do it yourself if you want an AST),

but it probably will in a future version. Sometimes this is considered

part of either the parsing step or the semantic analysis step.

AST Creation:

This step is optional and is only sometimes performed by automatic parsers.

Goldie doesn't currently perform this (so you'll have to do it yourself if you want an AST),

but it probably will in a future version. Sometimes this is considered

part of either the parsing step or the semantic analysis step.

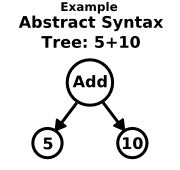

In this step, the parse tree is converted into an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree). An AST is like a parse tree, but it more closely resembles the way humans understand the code. For instance, the parse tree representation of 5 + 10 can be somewhat complex, unintuitive and highly dependent on the language's grammar. But an AST would most likely represent it very naturally: With one node for "Addition" that contains two subnodes, one for "5" and one for "10".

An XML/HTML DOM is a good example of an AST. For another example, see the output of GenDocs's -ast flag.

-

Semantic Analysis:

This step is generally NOT performed by automatic parsers.

The user of such tools has to perform this step on their own because it's

not as easily formalized as lexing, parsing or AST creation.

Semantic Analysis:

This step is generally NOT performed by automatic parsers.

The user of such tools has to perform this step on their own because it's

not as easily formalized as lexing, parsing or AST creation.

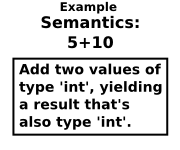

In this step, the parse tree or the AST is analyzed and actual meaning is determined. This often involves extra error checking. For instance, in statically-typed languages, the type system exists in the semantic analysis phase. This step is also where type-mismatch errors and "undefined function/variable" errors are generated. Semantic analysis can be thought of as anything in the frontend that isn't formally defined by the language's grammar.

See the GenDocs source for an example of lexing/parsing with Goldie and then constructing an AST tree and performing semantic analysis.

Using a Parsing Tool

Parsing tools such as Goldie only deal with the frontend. But not the entire frontend: Just the lexing, parsing, and sometimes AST creation parts. The rest still has to be written by the user of the parsing tool.

There are a variety of parsing tools available, and they differ in various ways, such as: what parsing algorithm they use, what language is used to perform the parsing (ie, the "host" language), how the grammar is defined, and what special tools can be used.

Goldie is compatible with the GOLD Parsing System, and both use DFA for lexing and LALR(1) for parsing. GoldieLib is designed to be used in programs written in the D programming language (D version 2). But, the GOLD/Goldie systems are designed to be easily extended to other host languages via GOLD-compatible "engines", many of which are available besides GoldieLib.

See the Goldie Overview page for an overview of using Goldie, or the Beginner's Tutorial page for a full tutorial.

The GOLD website has a great tutorial on Getting Started With Parsing that's geared towards GOLD. It's applicable to Goldie as well, since the two are compatible.

The Next Step

Next: Goldie Overview

Or, skip to the Beginner's Tutorial.

More Information

There are many resources for learning more about compilers and the computer science theory behind them. Here are some recommended resources for getting started:

Web Pages:

-

GOLD Parsing System: Articles, Links and Much More

Many useful articles and links. I've personally found these very helpful.

Books:

-

Crafting a Compiler

ISBN-10: 0136067050

ISBN-13: 978-0136067054

All books on compiler theory I've seen target an audience of mathematicians, computer scientists and/or students of such fields, rather than programmers. But this is by far the most programmer-friendly one I've come across. I found it to be of immense help when writing GRMC: Grammar Compiler. -

Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools

(ie, "The Dragon Book")

ISBN-10: 0321486811

ISBN-13: 978-0321486813

Widely considered the classic text on compiler theory. It is, however, one of the most heavily mathematician/computer-scientist-oriented compiler books out there. But, while it's far from being the most programmer-friendly, it is very detailed and thorough. -

GOLD Parsing System: Compiler Books

Links to some other books on compiler theory, and also other parsing systems.